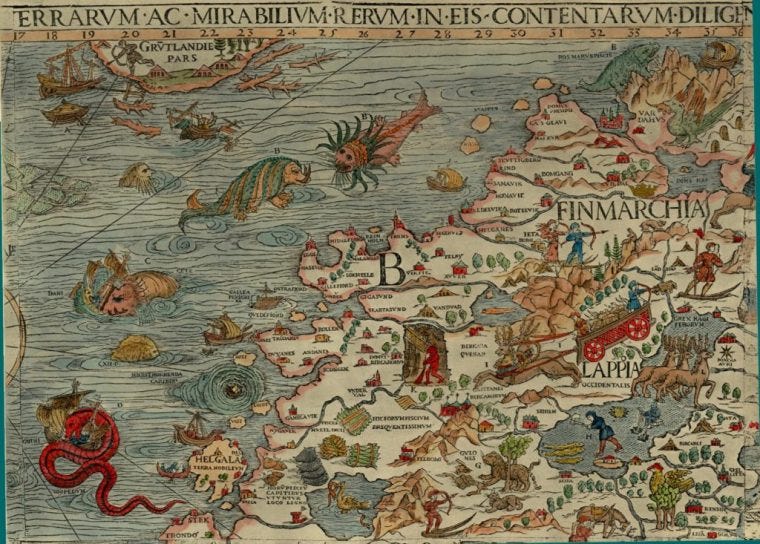

It’s the 16th century and you’re the navigator of a Scandanavian Galley bound for deep sea trade. Europe disappears into the horizon behind you as unscroll the latest map, drawn by Olaus Magnus, across the table: every good navigator needs a good map.

Past the intricate design of the land formations ranging from Scandia, Finmarchia, and Botnia lies the Atlantic Ocean, a great waterbody vastly unexplored. The water you’re now barreling toward is depicted as filled with creatures of size, mystique, and power.

However, the skeptic in you wants to believe Magnus might’ve overestimated the danger of the region. After all, the known regions of the ocean didn’t reveal a Cthulu or Kraken. With the treasures of your ship and your life at stake, you decide to hide this information and call in the crew.

You’re berated with questions about the length of the trip, the direction you’re heading, and any weather hazards.

“Despite general oceanic currents and storms, the route should be much faster than the usual detour. The only downside is we’re wading unmarked waters.”

As you calmly map out the voyage, the men of the crew ease up. Drinks, card games, and arm wrestling commence as the sun begins to set.

In the center of this crew filled with comfort, lies but a boy filled with concern. He taps on your shoulder and asks:

“How safe is this voyage?”

This question amuses the men, who cheerfully drink at the boy’s seemingly obvious question.

”Safety? We’re merchants, there’nt be a pirate in this ocean brave enough to sink us!”

As men laugh and return to their games, you sit frozen. The seriousness of your face startles one sailor’s confidence.

”Right navigator? Everything’s okay?”

Says the sailor unsure how honest his belief is.

”Right. Where we’re rowing no pirate would dare sail.”

Before the sailor can breathe a sigh of relief, the once-still waves quake. The ship is now baring 40-foot storm surges, as wind and rainfall pellets the galley’s hull. There’s a flash of lightning and the roar of thunder in the distance.

”Unfortunately, man is not our enemy.”

The room full of sailors sober up from this declaration as silence fills the air. Just in time to catch a harrowing noise outside.

”AHHHHHHHHHHH”

A scream from the starboard alerts the crew. They open the doors to see a giant silhouette appear in the lightning-filled sky. Behind this colossal shadow, emerges winged, scaled, and fanged creatures from the depths of imagination. The wind slams the door closed and the crew turns to you once more. You swing open your desk drawer and again unscroll your map across the table, pointing to the center of the Atlantic Ocean.

To the shock of all, amorphous monsters of all colors and sizes fill the unmarked waters you tread. Goliath fish, multiheaded lizards, and whirlpools the size of cities. To the horror of the room, you utter the worst words a sailor could hear…

”Here be Dragons.”

Dramatics aside, “Here be Dragons” has a reputation as far back as medieval Europe.

Whether the plurality of mapmakers utilized this phrase or the legend is exaggerated in our modern world, the phrase stands as a warning of the unknown. That in the unknown could be unprecedented danger; in a place of unknown scope, scale, species, and season, there could be dragons. Nonetheless, travelers be warned that the unknown is not a safe, or comforting place to be. What better way to convey this message than a giant drawing of a monster and ambiguous text in the vast uncharted section of the map?

We live in a world of increasing danger be it international conflict, domestic resource scarcity, insurrection, gun violence, terrorism, or extreme weather events. But the danger we ought to consider isn’t rare, novel, or even newsworthy. The danger we walk past daily, the unspoken rules we heed to avoid the dangers our mind might’ve never thought of.

You don’t need a fireman to tell you not to stick a fork in an electrical outlet, or a pilot to tell you not to open a plane door while in flight. Society has spent decades instilling within us all a common sense of danger: a red sign means stop, don’t play with fire, look both ways before you cross the street. These aspects of everyday life are hazardous, something that could be dangerous but poses no immediate threat if you avoid or properly use them.

Interestingly, this hasn’t always been the case. Many hazards of today were unknown in the past. Smoking was seen as good for your health, fatty diets weren’t widely known to be bad for the heart, and some believed bloodletting was effective medicine while showering was deemed witchcraft. In a world before cars, there was no need to look both ways while crossing, a world before electricity had no concern about where you stab a metal fork, and a world without planes couldn’t fathom the potential dangers of high-altitude and high-speed door opening. How society interacts with danger is not absolute, it has changed over time as our understanding of safety or hazard has evolved. With new hazards and new knowledge of old hazards, perceptions of a common sense of danger change.

After sailors or soldiers explore a region, no longer “Here be dragons”, here be Madagascar or the New World. Through exploration, Terra Incognita (land unknown) becomes just another destination on the map. But the initial communication of the unknown, cartographically, was necessary to convey potential danger to the everyday voyager. The warning served as protection from a danger well beyond their means.

In modern times we’ve certainly found better ways than cryptic phrases. Be it blank canvases, question marks, or a grid to showcase a lack of information. After all, it’s one thing to lack accurate geographical information, it’s another thing to suggest the presence of the supernatural. Moreover, the many dangers of our world are represented with numbers, letters, or symbols. Creating a system of hazard signs and warnings needed to protect people. But who’s to say the convenience of shared communication will last forever?

Today, modern historians gaze into the past to wonder about the meanings behind “here be dragons” and how danger was communicated. What if tomorrow, our descendants stumble upon the world and question what our old symbols, words, and signage mean? What if some modern danger, becomes an unknown entity of the future? How could we communicate to the year 2500, to warn them of the dangers of the modern world?

Welcome,

I’m The Librarian and you are reading The Garden Library. This is a blogcast that tackles a variety of topics with a skew towards climate and environmental policy. This is Chapter 1, Page 2 and we are discussing the “universality” of danger assessment.

Codes for Hazard

The other day I found myself staring at one of those NFPA Color Diamonds that identify how hazardous something is. Each color represents a different hazard: Health(Blue), Fire(Red), Instability(Yellow), and Specific(White). Within 3 colors is a number (0-4) to represent the severity of the hazard, with 0 being safe, and 4 being extremely hazardous or deadly. While the white diamond has a symbol that specifically identifies the material type.

The NFPA diamond itself is only about 70 years old, but it isn’t a widely identifiable or known warning to the public. While I may have the knowledge and experience to be aware of these codes, the overwhelming majority of the population is not. I wondered how the average person is supposed to be aware of just how dangerous something is if the warning sign itself isn’t common knowledge. When barrels or trucks containing dangerous substances spill, or collapse. These are the only warnings of the nature of danger a community is exposed to, and most people can’t read them.

This foundation led me to a question: How can we ensure danger and hazard are effectively communicated across knowledge, culture, and time?

History of Hazard Codes

Across the 20th century, from the world wars to the Cold War weapons race, hazards of all kinds were becoming more common and more dangerous. Radioactive material, explosive devices, flammable liquids, poisonous gasses, and even more mundane objects like cleaning sprays and pesticides, all house hazardous substances.

Governments and companies alike needed to develop methods of warning the public and professionals of these dangers. A quick Google search could showcase the thousands to millions of different warning designs in use, each with its meaning.

Most famously, the skull and crossbones symbol of today is used to convey deadly, or poisonous hazards. However, only a few hundred years ago it was used to mark graveyards and tombstones and simultaneously was the moniker of pirates. A hazardous bin with a skull and bones to the 17th century human might be seen as belonging to a pirate, or being a tombstone of sorts. This interpretation warrants a drastically different response and interaction, than if interpreted as poisonous.

Conversely, the 21st-century human walking past a 17th-century Christian cemetery might confuse the skull and bones for the region being poisonous and unfit to enter. Even more interestingly, the symbol could be entirely meaningless to a person from the 3rd century.

As we cross time and cultures it’s clear that once modern representations of dangers aren’t enough. But is there a way to more completely convey danger to people of all kinds?

Hostile Architecture attempts to offer a solution.

The Science of Bad Vibes

The style is most commonly known for its dehumanizing and cruel use by the ruling class. The placement of pikes, bumps, or groves on park benches and street corners to deter the unhoused or whatever pigeon that dares perch there.

Despite its bad rep, hostile architecture is a much more fruitful and comprehensive venture. The design of bad spaces, bad vibes, and unfriendliness, that influence behavior has interesting implications for danger.

Think…

Why do spiked benches make us feel unwelcome?

Why does being at the edge of a high place elicit a bone-chilling reaction?

Why do we avoid the dark, or the deep ocean, or find space unnerving?

Fear. Of all human emotions, fear is one of the most potent. How fear influences action, and importantly inaction have profound implications for hostile architecture.

Artists, and designers throughout history have invested creative energy into generating artificial feelings of fear or danger. In doing so, they’ve come to realize ways in which you can reach all people.

A jumpscare works on everyone, it evokes an artificial sense of danger and as a result, elicits a fear response. This occurs, not by relying upon methods of communication subject to change over time, but because of instinctual cues.

Darkness, Alieness, Blood, Loud Noise, Speed, High Places, and the Unknown, are all instinctually bad news. Historically, these types of cues would always signal genuine danger and warrant caution and fear. Be it due to a predatory creature, injury, or environmental risk.

We are hardwired to react to these cues, without a necessary cognitive thought. We react so fast because, at an instinctual level, we know to be wary of these cues. Hostile architects, taking this principle into account, can use this to their advantage. Instead of communicating a region is radioactive, or poisonous, build an ominous gruesome scene that’d make any person steer clear.

To note, this very example and image is tackled more in-depth in the supporting documents in the comment section. Be sure to check out the JSTOR article.

In a far-flung future, when current modes of communication are obsolete and incompatible. These instinctual cues will remain, allowing us to predict and design based on how people will react to them.

The Bigger Picture

When I look at our world which is gradually progressing towards sustainability, towards a greener, cleaner, and safer future, I wonder what will become of the danger. The many substances we can’t reuse, recycle, or dispose of. The many biochemical remnants of the past that lie in barrels, boxes, and bottles will outlast us all. Our current hazard communication system would have us blindly trust the transfer of modern symbols, languages, and conventions across millennia. We are potentially exposing the future to dangers beneath their noses, with no possible way of knowing.

Hostile design could allow us to properly house, and protect these biochemical time capsules in places the future won’t seek to explore. To build spaces of danger and dystopia to protect not just humans, but our neighbors in this ecosystem from uncovering poison and radioactivity.

There’s a reason medieval humans chose dragons and monsters to convey danger, instead of giant words of warning. We naturally know a region of Lovecraftian creatures is not a place we’d like to be, the weirder the drawing the more pronounced the sense of danger.

More fundamentally, the decision to use drawings of monsters was one of accessibility. If I wanted to read a map in Chinese, Swedish, or Amharic, unless I knew the language I’d be ignorant of the written dangers. Drawings and symbols do offer a means of communication across languages. However, even symbols and warnings in English often require a degree of understanding and knowledge, above what the majority of English possess, to get the memo. To call back upon the image of the NFPA diamond, did you know a “W” in the white diamond meant the substance violently reacts with water? Something so simple would’ve flown over most of our heads without the specific experience and information to decode the symbol.

As we progressed further as a society and developed more technically advanced materials, so too did the quantity and potency of hazardous materials increase. At a time of mass climate change that threatens our descendants, we mustn’t forget to look out for them when it comes to the forever chemicals and waste we release into the world. This conclusion also encourages us to rethink danger assessment across the globe, to protect disadvantaged populations more effectively.

Think of children, the elderly, the poor, and those living outside established English-speaking society. If we drop our tankers, float our chemicals, or dispose of our waste in their proximity. How could they go about ensuring their safety, if they can’t even identify the danger?

While hostile architecture at large is much harder to utilize on a small scale of products, its principles are applicable everywhere. If we make our Tide pods less like candy, and more horrific, fewer children would end up eating them. If chemical cleaners looked less like soda, and more like a disgusting mixture of “don’t drink”, fewer people would.

Now obviously, putting spikes on Twinkies or blood stains on vapes won’t fix everything. There will always be incidents of those who end up in contact with hazards, and who knows to what extent common perceptions of “hostile” won’t evolve over hundreds of years. For all we know giant black spikes coming out of the ground would be a stylistic preference and not the otherworldly horror we see it as. But before we can think about how to solve these problems we must first recognize them as problems.

Across your everyday life, how many hazards do you walk past unknowingly? Are you aware of the people, or living things, who could be ignorant to the dangers you recognize? Could you think of ways to communicate more effectively, without words or symbols, but with universal feelings? Not just for the betterment of today, but for the gratitude of tomorrow.

I appreciate your time here at The Garden Library. I invite you to subscribe and explore all of the different offerings.

Until the next page unfolds.

Supporting Documents:

JSTOR

https://daily.jstor.org/can-we-use-art-to-warn-future-humans-about-radioactive-waste/